tHE BIG DEBT CYCLE

Article n.2: how debt crises begin

Welcome to the second instalment of our series on Major Debt Crises.

In the previous article (Check it out here), we explored the concepts of credit and debt, examining their fundamental role within the modern economic system.

In this new chapter, we will delve into how Debt Crises originate and why they affect such diverse economies across the globe.

However, before continuing our discussion, it is important to answer a fundamental questio, one that may arise even among seasoned professionals:

What is an economic cycle?

According to Ray Dalio, one of the most influential investors and economists of the past four decades a cycle is defined as:

“Nothing more than a sequence of events driven by economic logic that regularly repeats over time.”

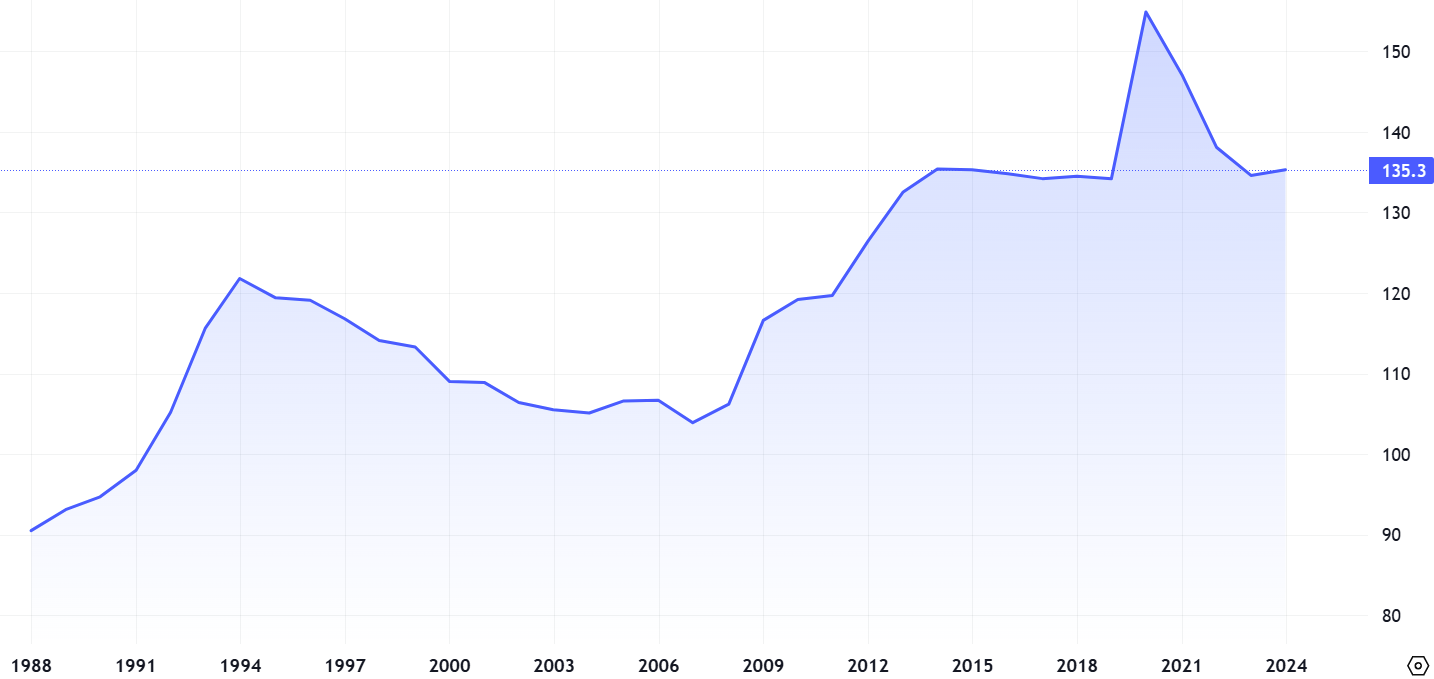

In economic terms, cycles emerge and end primarily as a result of expansions and contractions in credit.

Fluctuations in credit are, in turn, influenced by:

- The economic policies enacted by governments

- The actions of central banks, which regulate the money supply in the economy.

Put simply, every time a debt is incurred, a new cycle is set into motion.

The mechanism is straightforward: when I borrow a sum of money, I commit to repaying it in the future, thus initiating a predictable chain of events such as interest payments (monthly, quarterly, or annually) and the eventual repayment of the principal.

Now, imagine the borrower is not an individual, but a state. The mechanism remains the same, though the transactions are significantly more complex, and far larger in scale.

When a loan is issued, it fuels spending. Through bank deposits, financial institutions can then extend additional credit to other borrowers. This process stimulates economic growth: households and businesses purchase goods, services, and financial assets on credit, expecting to repay in the future.

However, as credit continues to expand, asset prices rise (often further propelled by expansionary monetary policies adopted by central banks).

This process becomes self-reinforcing until it hits a saturation point:

The cycle peaks when asset holders, due to events such as declining corporate profits or falling prices, can no longer sustain their debt obligations.

What happens next?

In many cases, additional debt is taken on to repay existing obligations, a solution that may appear convenient at first.

Often, the peak of the cycle coincides with tighter monetary policy (i.e. interest rate hikes by the central bank). While such policy does not directly cause the downturn, it frequently precedes it by restricting the availability of credit, thereby accelerating the decline.

As no economy can grow indefinitely, a gradual deterioration in repayment capacity follows:

- Interest payments become increasingly burdensome;

- The issuance of new credit slows, hampered by central bank intervention or stricter lending requirements;

- Financial institutions exert mounting pressure on borrowers.

This deterioration process is also self-reinforcing, exposing:

- Financial institutions, which become vulnerable due to excessive leverage;

- Economically fragile borrowers, who face an increased risk of default.

So, how can disaster be avoided?

As Ray Dalio notes:

“The key to managing a debt crisis well lies in the ability of policymakers to correctly employ the policy levers available to them — and in having the authority to do so.”

In times of acute crisis, the speed and effectiveness with which these tools are deployed determine the severity and duration of the downturn.

In the next chapter of the series, we will examine how Debt Crises unfold in practice and what instruments (austerity, default, money creation, and credit/debt transfers) can be used to mitigate their effects and support a sustainable recovery.

THANK YOU!

Website you may want to see:

- One of Dalio’s websites: https://economicprinciples.org/

- The “Big Debt Crises” PDF: https://www.bridgewater.com/big-debt-crises/principles-for-navigating-big-debt-crises-by-ray-dalio.pdf

Leave a Reply